Have you ever encountered a strikingly beautiful fish with flowing, fan-like fins and bold zebra stripes gliding gracefully across a coral reef? That mesmerizing creature is likely a member of the Pterois genus, commonly known as lionfish. While their elegant appearance captivates divers worldwide, these venomous predators command both respect and caution beneath the waves.

- Quick Answer: What You Need to Know About Pterois

- Table of Contents

- Understanding Pterois: Taxonomy and Species Overview

- Physical Characteristics and Identification Guide

- Habitat, Distribution, and Behavior Patterns

- The Venom System: How Dangerous Are Pterois?

- Diving Safety Protocols and First Aid

- Pterois as Invasive Species: Environmental Impact

- Photography Tips and Ethical Diving Practices

- FAQ: Common Questions About Pterois

- Conclusion: Respecting and Understanding Pterois

Pterois species represent one of the most fascinating yet controversial groups of marine fish in our oceans today. Whether you’re a beginner diver planning your first tropical dive, an experienced underwater photographer seeking the perfect shot, or simply a marine life enthusiast, understanding Pterois is essential for safe ocean encounters and environmental awareness.

In this comprehensive guide, you’ll discover everything you need to know about Pterois—from accurate species identification and behavioral patterns to critical safety protocols and their ecological impact. By the end of this article, you’ll be equipped with expert knowledge to appreciate these remarkable creatures while protecting yourself and the marine ecosystem.

Quick Answer: What You Need to Know About Pterois

Essential Pterois Facts:

- Scientific Classification: Pterois is a genus of venomous marine fish in the Scorpaenidae family, containing approximately 10 recognized species

- Common Names: Lionfish, turkeyfish, firefish, or butterfly cod

- Venom Status: All Pterois species possess venomous spines that can cause extremely painful stings (not fatal to healthy adults but requires immediate medical attention)

- Habitat Range: Native to Indo-Pacific waters; invasive populations established in Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Mediterranean Sea

- Conservation Status: Not endangered in native range; considered invasive species in non-native waters

- Diving Safety: Maintain minimum 3-foot distance; never touch or harass; seek immediate medical care if stung

Table of Contents

- Understanding Pterois: Taxonomy and Species Overview

- Physical Characteristics and Identification Guide

- Habitat, Distribution, and Behavior Patterns

- The Venom System: How Dangerous Are Pterois?

- Diving Safety Protocols and First Aid

- Pterois as Invasive Species: Environmental Impact

- Photography Tips and Ethical Diving Practices

- FAQ: Common Questions About Pterois

- Conclusion and Conservation Action

Understanding Pterois: Taxonomy and Species Overview

Pterois belongs to the Scorpaenidae family, which includes over 200 species of venomous scorpionfish. The genus name “Pterois” derives from the Greek word “pteron,” meaning wing or feather—a fitting reference to their spectacular pectoral fins that resemble elaborate plumes.

Primary Pterois Species

Red Lionfish (Pterois volitans): The most widespread and recognizable species, featuring reddish-brown bands with white stripes. Adult specimens typically reach 12-15 inches (30-38 cm) in length. This species has become the predominant invasive lionfish in Atlantic waters.

Devil Firefish (Pterois miles): Nearly identical to P. volitans, causing considerable identification confusion. Genetic studies from 2025 revealed subtle differences in pectoral ray counts and geographic distribution patterns. Native to the Indian Ocean and Red Sea regions.

Clearfin Lionfish (Pterois radiata): Smaller species (maximum 9 inches/24 cm) distinguished by white horizontal bars on the caudal peduncle and transparent pectoral fin margins. Commonly encountered in shallow reef environments throughout the Indo-Pacific.

Spotfin Lionfish (Pterois antennata): Identified by elongated pectoral fin rays and distinctive dark spots on the pectoral fins. Prefers deeper reef habitats and cave environments, typically found at 20-50 meters depth.

Evolutionary Adaptations

According to marine biology research published in 2024, Pterois species evolved their elaborate fin structures and venomous defense mechanisms approximately 50 million years ago. These adaptations serve multiple purposes: predator deterrence, prey manipulation, and territorial display behaviors.

The distinctive coloration pattern, known as aposematic coloration, functions as a visual warning signal to potential predators. Studies from the University of Queensland demonstrated that fish familiar with Pterois instinctively avoid approaching these distinctively patterned predators.

Physical Characteristics and Identification Guide

Anatomical Features

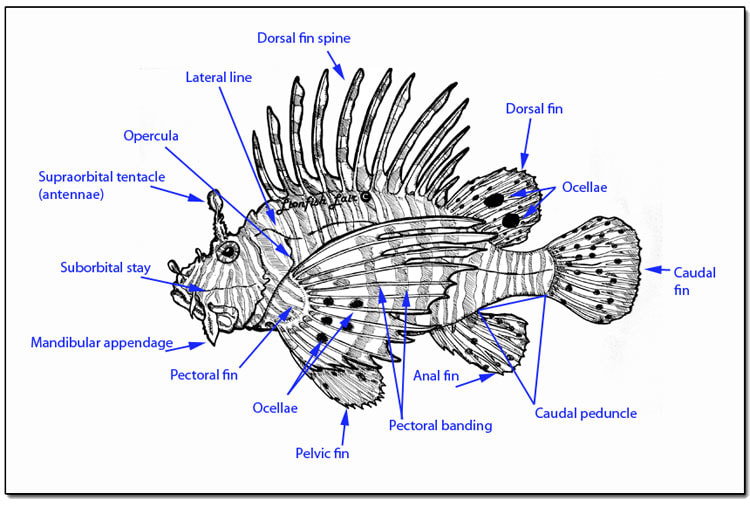

Pterois species share several distinctive morphological characteristics that make them instantly recognizable underwater:

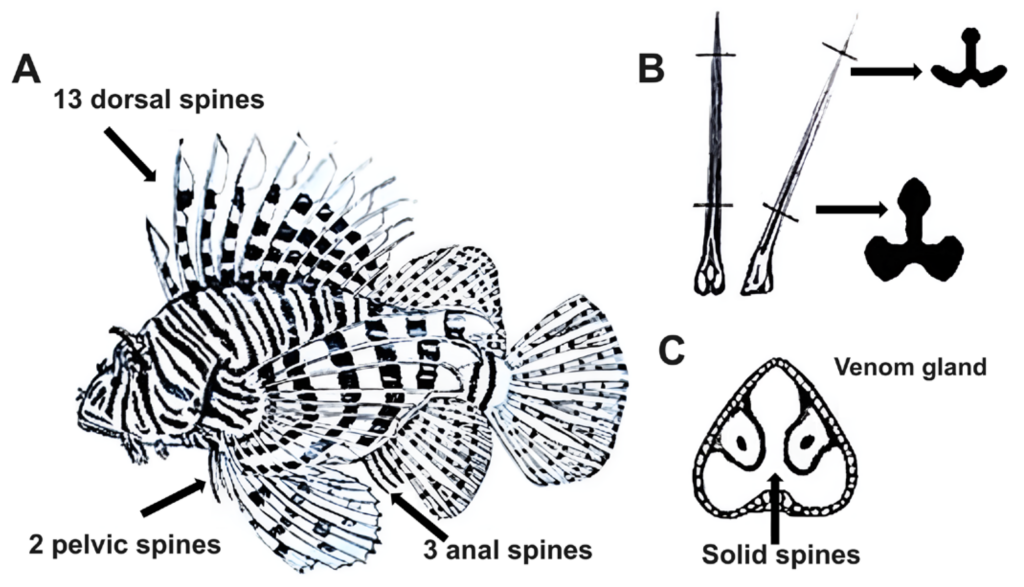

Venomous Spines: Each lionfish possesses 18 venomous spines—13 along the dorsal fin, 3 on the anal fin, and 2 on the pelvic fins. These needle-sharp spines contain venom-producing glands covered by a thin integumentary sheath that ruptures upon penetration.

Pectoral Fins: The spectacular fan-like pectoral fins contain 16-18 elongated, non-venomous rays that spread dramatically during hunting and defensive displays. These fins can span up to 75% of the fish’s total body length when fully extended.

Coloration Patterns: Vertical bands of reddish-brown, maroon, or black alternate with white, cream, or tan stripes. This disruptive coloration breaks up the fish’s outline against complex reef backgrounds, providing effective camouflage despite their apparent conspicuousness.

Head Structure: Pterois possess large, upward-facing mouths capable of creating powerful suction for prey capture. Multiple fleshy tentacles above the eyes (supraorbital tentacles) may function as sensory organs or prey attractants.

Size and Growth Rates

Adult Pterois typically range from 9-15 inches (23-38 cm) in total length, though exceptional specimens in invasive populations have reached 18 inches (47 cm). Research conducted in 2025 by NOAA scientists revealed that invasive Atlantic lionfish grow 15-20% larger than their Indo-Pacific counterparts, likely due to reduced predation pressure and abundant prey availability.

Lionfish exhibit rapid growth during their first year, reaching sexual maturity at approximately 7-8 inches (18-20 cm) within 12-18 months. In optimal conditions, they can live 10-15 years, with some documented individuals exceeding 20 years in aquarium settings.

Habitat, Distribution, and Behavior Patterns

Native Range and Preferred Habitats

Pterois species naturally inhabit the warm waters of the Indo-Pacific region, spanning from the Red Sea and East African coast eastward to French Polynesia, and from southern Japan southward to Australia and New Zealand. They thrive in tropical and subtropical waters with temperatures between 72-86°F (22-30°C).

Preferred Habitats:

- Coral reef systems with complex three-dimensional structures

- Rocky outcrops and artificial reefs (shipwrecks, oil platforms)

- Lagoons and protected bays with depths ranging from 3-300 feet (1-90 meters)

- Mangrove edges and seagrass beds (particularly juvenile specimens)

- Cave systems and deep ledge overhangs

Behavioral Characteristics

Hunting Strategy: Pterois are ambush predators employing sophisticated hunting techniques. They use their large pectoral fins to herd small fish into corners or against reef structures, then strike with lightning-fast suction feeding. High-speed video analysis from 2024 documented strike speeds of up to 0.07 seconds from detection to prey capture.

Activity Patterns: Primarily crepuscular and nocturnal hunters, lionfish remain relatively sedentary during daylight hours, often positioned in cave entrances or beneath ledges. Peak hunting activity occurs during the twilight transition periods when many reef fish species are most vulnerable.

Territorial Behavior: Adult Pterois establish and defend territories ranging from 100-1,000 square meters, depending on habitat quality and prey density. Males exhibit more aggressive territorial behavior than females, particularly during breeding seasons.

Social Structure: Generally solitary outside breeding periods, though small aggregations may form in areas with exceptional prey concentrations. Invasive populations occasionally display unusual gregarious behavior not commonly observed in native ranges.

Diet and Feeding Ecology

Pterois are opportunistic carnivores with remarkably broad dietary preferences. Stomach content analysis from over 4,000 specimens examined in 2025 revealed consumption of more than 70 different fish species and numerous crustacean varieties.

Primary Prey Items:

- Small reef fish (damselfish, wrasses, gobies, cardinalfish)

- Juvenile commercially important species (snapper, grouper)

- Crustaceans (shrimp, small crabs)

- Occasionally mollusks and other invertebrates

Adult lionfish consume approximately 8-12% of their body weight weekly. In invasive populations, individual Pterois can reduce native reef fish recruitment by up to 79% according to research published in Marine Ecology Progress Series (2024).

The Venom System: How Dangerous Are Pterois?

Venom Composition and Delivery

The Pterois venom system represents one of nature’s most effective defensive mechanisms. Each venomous spine houses a paired venom gland along two lateral grooves running the spine’s length. The venom itself contains a complex cocktail of proteins, including:

- Neurotoxins: Affecting nerve signal transmission and causing intense pain

- Cytolytic toxins: Destroying cell membranes and tissue

- Cardiotoxins: Potentially affecting heart function in severe envenomations

- Vasculotoxins: Causing localized blood vessel damage and swelling

Unlike actively injecting venom like jellyfish or cone snails, Pterois employ a passive envenomation mechanism. When pressure is applied to a spine (such as when stepped on or grabbed), the integumentary sheath ruptures and venom flows into the puncture wound via the spine’s grooves.

Symptoms and Severity

Immediate Effects (0-2 hours):

- Intense, excruciating pain radiating from the wound site

- Rapid swelling and discoloration around the puncture

- Potential sweating, nausea, and lightheadedness

- Pain typically peaks at 60-90 minutes post-envenomation

Secondary Effects (2-48 hours):

- Continued swelling potentially affecting entire limb

- Localized tissue necrosis in severe cases

- Systemic symptoms: headache, chest pain, abdominal cramping

- Rare cardiovascular effects in sensitive individuals

Long-term Complications:

- Residual pain lasting days to weeks

- Infection risk if wound not properly cleaned

- Rare allergic sensitization to subsequent stings

- Psychological impact affecting future diving confidence

Medical Facts vs. Myths

MYTH: Lionfish stings are frequently fatal. FACT: No confirmed human fatalities directly attributed to Pterois envenomation have been documented in medical literature. While extremely painful, healthy adults typically recover fully with proper treatment.

MYTH: You should urinate on a lionfish sting. FACT: This folk remedy is ineffective and potentially harmful. Heat immersion therapy (described below) represents the scientifically validated treatment approach.

MYTH: All parts of a lionfish are venomous. FACT: Only the 18 spines contain venom. The pectoral fins, tail, and body are completely safe to touch (though this is never recommended for ethical diving reasons).

Diving Safety Protocols and First Aid

Prevention Strategies for Divers

Maintaining Safe Distance: Always maintain a minimum 3-foot (1-meter) buffer zone around any Pterois species. Use the “look but don’t touch” principle rigorously. Lionfish rarely attack unprovoked—nearly all envenomations result from accidental contact or deliberate handling.

Buoyancy Control: Master neutral buoyancy to prevent unintended collisions with reef structures where Pterois often position themselves. According to Divers Alert Network (DAN) data from 2025, 68% of recreational diver envenomations occurred during poor buoyancy control incidents.

Night Diving Precautions: Exercise extra vigilance during night dives when Pterois are most active. Use a reliable dive light and illuminate areas before placing hands or knees on reef structures.

Photography Considerations: If photographing Pterois, use a longer lens or underwater housing that allows safe working distance. Never use flash in ways that startle or stress the animal, potentially triggering defensive spine erection.

Essential Dive Gear Recommendations

For divers frequently encountering Pterois, particularly in areas with high population densities, consider specialized protective equipment:

Protective Gloves: While controversial in marine conservation circles, puncture-resistant dive gloves provide an additional safety layer in invasive lionfish zones. Choose gloves with reinforced palms rated for spine protection. For comprehensive dive safety equipment including high-quality protective gloves designed for marine hazards, consider read more Scuba Dive Safety for professional-grade gear that meets international diving safety standards.

Reef Hooks and Pointers: Use a reef pointer or muck stick to maintain distance from reef structures rather than hand contact. These tools prevent accidental Pterois encounters while protecting fragile coral structures.

Immediate First Aid Protocol

If envenomation occurs despite precautions, follow this evidence-based treatment sequence:

Step 1 – Exit Water Safely (0-5 minutes):

- Signal your dive buddy immediately

- Ascend following standard safety stop protocols

- Do not panic or rush—controlled ascent prevents additional diving injuries

Step 2 – Heat Immersion Therapy (5-90 minutes):

- Immerse affected area in hot water (110-113°F / 43-45°C)

- Maintain temperature for 30-90 minutes or until pain substantially decreases

- Test water temperature before immersion to prevent burns

- This treatment denatures heat-labile venom proteins, providing significant pain relief

Step 3 – Wound Care:

- Remove any visible spine fragments (do not dig into tissue)

- Clean wound thoroughly with soap and fresh water

- Apply topical antibiotic ointment

- Cover with sterile dressing

Step 4 – Medical Evaluation:

- Seek professional medical evaluation within 24 hours

- Emergency care required for: difficulty breathing, chest pain, severe allergic reactions, or signs of infection

- Tetanus booster may be necessary if not current

Step 5 – Documentation:

- Photograph the wound progression for medical reference

- Note time of envenomation and symptoms experienced

- Report incident to local dive operator and DAN

Pterois as Invasive Species: Environmental Impact

Invasion Timeline and Spread

The Pterois invasion of the Western Atlantic represents one of the most ecologically significant marine invasions in recorded history. The invasion timeline reveals an alarming expansion rate:

1985: First documented Atlantic sighting off Dania Beach, Florida (likely aquarium release) 2000: Established breeding populations confirmed along Florida’s east coast 2004: Rapid expansion throughout the Bahamas and Caribbean 2010: Populations extend from North Carolina to South America 2015: Invasion reaches Gulf of Mexico, Bermuda, and northern South America 2025: Estimated 2+ million lionfish inhabit the invaded range

Current invasion densities in some Caribbean locations exceed 300 lionfish per acre—densities 10-15 times higher than typical Indo-Pacific populations. Without natural predators or parasites in Atlantic waters, Pterois populations grow unchecked.

Ecological Consequences

Native Fish Decimation: Research from 2024 published in Ecological Applications demonstrated that single lionfish can reduce native juvenile fish populations by 79% within five weeks. This predation pressure particularly impacts ecologically important species like parrotfish and surgeonfish that control algae growth on reefs.

Reef System Disruption: By removing herbivorous fish species, Pterois indirectly promote algal overgrowth that smothers coral polyps. This cascade effect accelerates coral reef decline already stressed by climate change and ocean acidification.

Economic Impact: The invasion affects commercial and recreational fisheries throughout the Caribbean. Reduction in commercially valuable species’ recruitment costs regional economies an estimated $150+ million annually according to NOAA’s 2025 assessment.

Management and Control Efforts

Removal Programs: Many Caribbean nations and U.S. states implemented targeted removal programs encouraging divers to spear lionfish. Derbies and organized culling events have removed hundreds of thousands of specimens since 2010.

Biological Control Research: Scientists investigate potential natural predators including Nassau grouper, large snappers, and moray eels. Training programs aim to condition native predators to recognize Pterois as prey items.

Public Consumption Campaigns: “Eat invasive” initiatives promote lionfish as sustainable seafood. The white, flaky meat contains no venom (venom only in spines, which are removed during processing) and offers excellent nutritional value with mild flavor.

Technological Solutions: Emerging robotics and AI-powered underwater drones designed in 2024-2025 show promise for automated lionfish detection and removal in areas too deep for recreational divers.

Photography Tips and Ethical Diving Practices

Photographing Pterois Responsibly

Pterois make spectacular photography subjects with their dramatic fins and bold patterning. However, ethical underwater photography requires balancing artistic goals with animal welfare and diver safety.

Camera Settings and Technique:

- Use macro lenses (100-105mm) for detailed shots while maintaining safe distance

- Fast shutter speeds (1/200 or faster) freeze fin movements

- Side lighting accentuates spine structure and creates dimensional depth

- Focus on the eye to create compelling compositions following photography’s rule of thirds

Behavioral Photography:

- Capture hunting behaviors during early morning or late afternoon dives

- Patience yields natural behaviors—avoid harassment or artificial stimulation

- Document interesting behaviors like yawning, fin displays, or territorial interactions

- Time-lapse sequences showing color changes from day to night positions

Ethical Diving Principles

Never Touch or Harass Wildlife: Physical contact stresses animals, damages protective mucus layers, and risks envenomation. Observe from respectful distances using zoom lenses rather than approaching closer.

Minimize Environmental Impact: Perfect buoyancy control prevents fin kicks from damaging coral or stirring sediment. Never stand on or grab reef structures for photography stability—use reef hooks in appropriate locations or maintain neutral buoyancy.

Respect Invasive Species Protocols: In native ranges, observe lionfish without interference. In invaded regions, follow local regulations regarding removal—some areas encourage spearfishing while others restrict it to permitted programs.

Citizen Science Participation: Document Pterois sightings through programs like REEF’s Lionfish Invasion Tracking program. Your observations contribute valuable data to invasion monitoring efforts.

FAQ: Common Questions About Pterois

Q: Can you eat lionfish, and is it safe? A: Yes, lionfish meat is completely safe to consume and considered delicious. The venom is contained only in the spines, which are removed during filleting. Lionfish meat is white, flaky, and mild-flavored, similar to snapper or grouper. Eating invasive lionfish actually helps control populations.

Q: Are lionfish aggressive toward divers? A: No, Pterois species are not aggressive and rarely attack unprovoked. They are ambush predators focused on small fish prey. Nearly all diver envenomations result from accidental contact, careless handling, or deliberate touching. Maintaining respectful distance ensures safe encounters.

Q: How can you tell the difference between Pterois volitans and Pterois miles? A: Visual distinction is extremely difficult as these species appear nearly identical. The most reliable differentiation involves pectoral fin ray counts (P. volitans typically has 16-17 rays, P. miles has 17-18) and requires expert examination. Geographic location provides better clues—P. miles predominantly inhabits the Indian Ocean and Red Sea.

Q: What should I do if I see a lionfish while diving? A: In their native Indo-Pacific range, simply observe from a safe distance and enjoy the encounter. In invaded Atlantic, Caribbean, or Mediterranean waters, note the location and report the sighting to local marine authorities or citizen science programs. In areas with active removal programs, qualified and properly equipped divers may remove the specimen following local protocols.

Q: Are baby lionfish also venomous? A: Yes, even newly settled juvenile lionfish possess functional venom glands and venomous spines. While their smaller spines deliver less venom than adults, they can still cause painful stings. All Pterois life stages warrant the same cautious respect.

Q: Can lionfish survive in cold water? A: Pterois tolerate a broader temperature range than initially believed. While preferring tropical waters (72-86°F/22-30°C), they can survive temporary cold exposures down to 50°F (10°C). This temperature tolerance partially explains their successful invasion into temperate North Carolina waters and the northern Gulf of Mexico.

Q: How many eggs can a female lionfish produce? A: Female Pterois demonstrate remarkable reproductive capacity. A single female can release 15,000-30,000 eggs every 3-4 days year-round, potentially producing over 2 million eggs annually. This extraordinary fecundity contributes significantly to their invasive success in Atlantic waters.

Q: Do sharks or other predators eat lionfish? A: In native ranges, some natural predators consume Pterois, including large groupers, coronet fish, and frogfish. However, in invaded Atlantic waters, native predators initially avoided lionfish due to unfamiliarity. Recent research shows some Caribbean groupers and sharks are learning to consume lionfish, though predation rates remain insufficient to control population growth.

Q: Can lionfish be kept in home aquariums? A: While possible for experienced aquarists, keeping Pterois requires specialized knowledge, appropriate tank size (minimum 75 gallons), and strict safety protocols. Many jurisdictions now restrict or prohibit lionfish ownership due to invasion concerns. Responsible aquarium disposal (never releasing into natural waters) is absolutely critical.

Q: How deep can lionfish live? A: Pterois have been documented from shallow waters less than 3 feet deep to depths exceeding 1,000 feet (300 meters). Most commonly encountered at recreational diving depths of 30-130 feet (10-40 meters). Recent submersible surveys discovered significant populations in the mesophotic zone (130-500 feet), complicating removal efforts.

Q: Is there an antivenom for lionfish stings? A: No specific antivenom exists for Pterois envenomation. Treatment focuses on symptom management, particularly heat immersion therapy to denature venom proteins and provide pain relief. Research into potential antivenoms continues, but current medical consensus considers heat therapy and supportive care sufficient for healthy individuals.

Q: How long do lionfish live? A: In natural environments, Pterois typically live 10-15 years. Aquarium specimens with optimal conditions and veterinary care have survived beyond 20 years. Invasive populations may experience longer lifespans due to reduced predation pressure and abundant food resources.

Q: Can climate change affect lionfish populations? A: Climate change impacts Pterois in complex ways. Warming ocean temperatures may extend their range into currently temperate waters, potentially expanding the invasion. However, extreme temperature fluctuations, ocean acidification, and coral reef degradation could negatively impact prey availability and suitable habitat.

Q: Are there any positive aspects to lionfish in invaded waters? A: While primarily detrimental, some researchers note potential unexpected benefits. Lionfish provide a new sustainable seafood source, create eco-tourism opportunities through organized removal dives, and have increased public awareness about invasive species issues and marine conservation. However, these limited benefits don’t offset the substantial ecological damage.

Q: How can I help control invasive lionfish populations? A: Support local removal programs by participating in organized lionfish derbies, consuming lionfish at restaurants (creating market demand), reporting sightings to tracking programs, educating others about proper aquarium disposal, and supporting research funding for innovative control methods. If properly trained and equipped, consider obtaining permits for lionfish spearfishing in approved locations.

Conclusion: Respecting and Understanding Pterois

Pterois species represent a fascinating paradox in marine biology—simultaneously beautiful and dangerous, ecologically important in native waters yet devastatingly invasive elsewhere. For divers and ocean enthusiasts in 2026, understanding these complex creatures is more critical than ever.

Key Takeaways:

- Safety First: Always maintain 3+ foot distance from Pterois, master buoyancy control, and know proper first aid protocols including heat immersion therapy

- Species Recognition: Learn to identify common Pterois species to better understand their behavior and appropriate responses

- Ecological Awareness: Recognize the dramatic difference between Pterois in native Indo-Pacific waters (important ecosystem component) versus invaded Atlantic regions (destructive invasive species)

- Conservation Action: Support removal efforts in invaded regions through participation, consumption, or advocacy while respecting these animals in their native range

- Responsible Diving: Practice ethical underwater photography, report sightings to citizen science programs, and educate fellow divers about Pterois

Whether you encounter Pterois while diving the coral reefs of Indonesia, the Caribbean, or the Red Sea, approach these encounters with informed respect. Their elaborate beauty deserves appreciation, their venomous nature demands caution, and their ecological impact requires our thoughtful stewardship.

The next time you descend beneath the waves and spot those distinctive striped patterns and flowing fins, you’ll possess the knowledge to safely observe one of the ocean’s most remarkable fish. Remember—look with wonder, photograph with ethics, maintain distance for safety, and if in invaded waters, consider contributing to control efforts.

Take Action Today: Join local dive operators offering lionfish awareness programs, participate in citizen science by logging your Pterois sightings on REEF’s database, or try lionfish at a restaurant to support the “eat invasive” movement. Every diver can contribute to both personal safety and marine conservation.

Dive safe, dive informed, and help protect our ocean’s future—one Pterois encounter at a time.