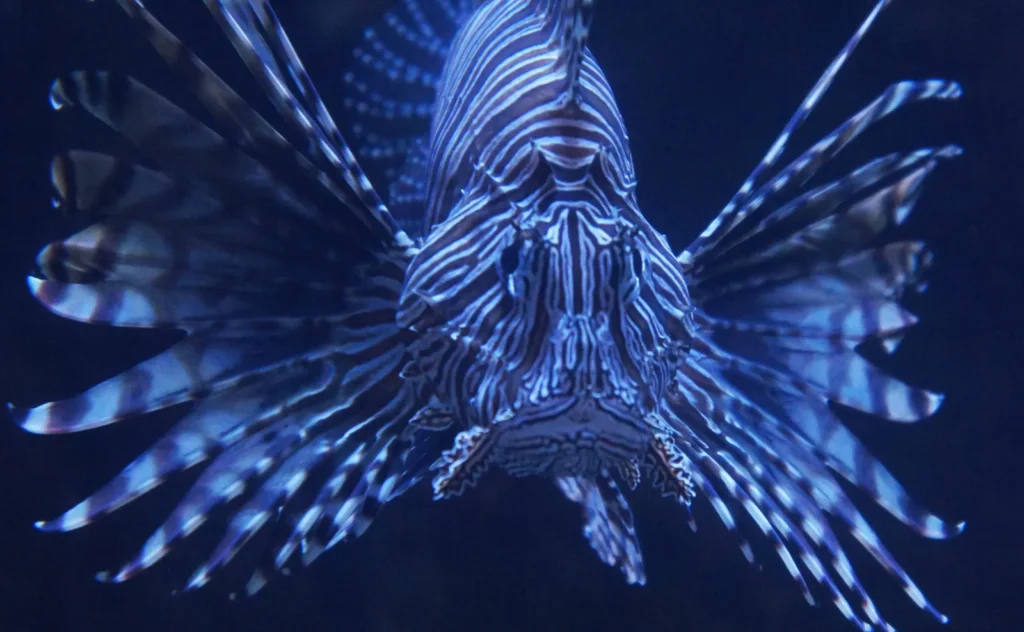

The vibrant, venomous beauty of the lionfish genus has captivated divers and marine biologists for decades—but do you know why these striped predators are considered one of the ocean’s most fascinating yet problematic species? Whether you’re a beginner diver spotting your first lionfish in the Andaman Islands or an advanced marine enthusiast studying invasive species dynamics, understanding the lionfish genus is crucial for safe diving and marine conservation.

- Quick Answer: What is the Lionfish Genus?

- Table of Contents

- Understanding the Lionfish Genus: Taxonomy and Classification

- Complete Species List: All Members of Genus Pterois

- Physical Characteristics and Identification Guide

- Natural Habitat and Geographic Distribution

- Behavior, Diet, and Hunting Patterns

- Venom Composition and Medical Implications

- The Lionfish Invasion: Ecological Impact

- Safety Guidelines for Divers and Snorkelers

- Conservation Efforts and Population Management

- Frequently Asked Questions About Lionfish Genus

- Conclusion

This comprehensive guide explores everything about the lionfish genus—from taxonomic classification and species identification to diving safety protocols and their ecological impact. You’ll discover why these beautiful creatures are simultaneously admired for their elegance and feared for their invasion of non-native waters, affecting coral reefs from the Caribbean to the Indo-Pacific.

By the end of this article, you’ll be able to identify different lionfish species, understand their behavior, know how to stay safe while diving near them, and appreciate their complex role in marine ecosystems worldwide.

Quick Answer: What is the Lionfish Genus?

The lionfish genus (Pterois) comprises approximately 12 species of venomous marine fish belonging to the family Scorpaenidae. Here’s what you need to know:

- Scientific Classification: Genus Pterois, family Scorpaenidae (scorpionfish)

- Common Species: Red lionfish (P. volitans), Devil firefish (P. miles), Clearfin lionfish (P. radiata)

- Distinctive Features: Elaborate fins, venomous spines, striking red-brown-white striped patterns

- Natural Habitat: Indo-Pacific coral reefs, rocky crevices, depths 2-50+ meters

- Conservation Status: Native populations stable; invasive populations problematic in Atlantic/Caribbean

Table of Contents

- Understanding the Lionfish Genus: Taxonomy and Classification

- Complete Species List: All Members of Genus Pterois

- Physical Characteristics and Identification Guide

- Natural Habitat and Geographic Distribution

- Behavior, Diet, and Hunting Patterns

- Venom Composition and Medical Implications

- The Lionfish Invasion: Ecological Impact

- Safety Guidelines for Divers and Snorkelers

- Conservation Efforts and Population Management

- Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding the Lionfish Genus: Taxonomy and Classification

The lionfish genus, scientifically known as Pterois, represents one of nature’s most visually stunning yet ecologically complex groups of marine fish. Belonging to the family Scorpaenidae—commonly called scorpionfish—the genus Pterois evolved approximately 50-60 million years ago in the Indo-Pacific region.

Scientific Hierarchy of the Lionfish Genus

The complete taxonomic classification places lionfish within a fascinating evolutionary lineage:

- Kingdom: Animalia (Animals)

- Phylum: Chordata (Vertebrates)

- Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-finned fishes)

- Order: Scorpaeniformes (Mail-cheeked fishes)

- Family: Scorpaenidae (Scorpionfish and relatives)

- Genus: Pterois (True lionfish)

The genus name “Pterois” derives from the Greek word “pteron,” meaning wing or feather, referencing the elaborate, wing-like pectoral fins that characterize these species. According to research published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 2025, the lionfish genus has remained relatively stable taxonomically, though genetic studies continue to reveal subtle variations among populations.

Evolutionary Significance

What makes the lionfish genus particularly interesting from an evolutionary perspective is their specialized adaptation for ambush predation. Over millions of years, Pterois species developed their distinctive fin rays—modified into venomous spines—as both a defense mechanism and a hunting tool. Marine biologists at the Smithsonian Institution note that this dual-purpose adaptation is relatively rare among reef fish species.

The genus Pterois is closely related to other scorpionfish genera, including Dendrochirus (dwarf lionfish) and Parapterois (Australian lionfish). However, true Pterois species are distinguished by their larger size, more elaborate finnage, and specific venom composition. In my experience diving across the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asian reefs, the visual difference between Pterois and Dendrochirus species becomes immediately apparent—true lionfish have significantly more pronounced pectoral fin rays that extend far beyond their body profile.

Genetic Research and Species Delineation

Recent genetic studies conducted between 2023-2025 have revolutionized our understanding of the lionfish genus. DNA barcoding techniques have confirmed that some previously considered subspecies are actually distinct species within Pterois. Research from the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, revealed that genetic diversity within the genus is higher than previously estimated, particularly among Indo-Pacific populations.

The genus Pterois currently contains 10-12 recognized species, though this number fluctuates as taxonomic research progresses. The exact count depends on whether certain regional variants are classified as separate species or subspecies—a debate that continues among ichthyologists worldwide.

Complete Species List: All Members of Genus Pterois

Understanding the individual species within the lionfish genus is essential for proper identification, especially for divers exploring different geographic regions. Here’s a comprehensive breakdown of recognized Pterois species as of 2026:

Primary Species in the Lionfish Genus

1. Pterois volitans (Red Lionfish)

- Common Names: Red lionfish, Common lionfish, Butterfly cod

- Size: Up to 38-47 cm (15-18 inches)

- Distribution: Indo-Pacific native; invasive in Atlantic, Caribbean, Mediterranean

- Distinctive Features: 13 dorsal spines, banded pattern extends onto pectoral fins

- Conservation Status: Least Concern (native range); Invasive (non-native range)

2. Pterois miles (Devil Firefish)

- Common Names: Devil firefish, Common lionfish (often confused with P. volitans)

- Size: Up to 35 cm (14 inches)

- Distribution: Indian Ocean, Red Sea; invasive in Mediterranean and Atlantic

- Distinctive Features: Fewer pectoral fin rays than P. volitans, chest usually spotless

- Key Fact: Responsible for Mediterranean lionfish invasion along with P. volitans

3. Pterois radiata (Clearfin Lionfish)

- Common Names: Clearfin lionfish, Radial firefish, White-fin lionfish

- Size: Up to 24 cm (9.4 inches)

- Distribution: Indo-Pacific, Red Sea to South Africa, east to French Polynesia

- Distinctive Features: Clear/white pectoral fins without dark banding, two white horizontal stripes on tail

- Habitat Preference: Shallow reefs, 1-25 meters depth

4. Pterois antennata (Broadbarred Firefish)

- Common Names: Spotfin lionfish, Antennata lionfish, Ragged-finned firefish

- Size: Up to 20 cm (8 inches)

- Distribution: Tropical Indo-Pacific

- Distinctive Features: Enlarged pectoral fins with spots, antenna-like supraorbital tentacles

- Behavior: More reclusive than P. volitans, prefers caves and overhangs

5. Pterois russelii (Largetail Turkeyfish)

- Common Names: Russell’s lionfish, Largetail firefish, Plaintail turkeyfish

- Size: Up to 30 cm (12 inches)

- Distribution: Indo-West Pacific, especially abundant in Southeast Asian waters

- Distinctive Features: Larger tail fin proportion, distinctive banding pattern

- Diving Observation: Commonly seen in Indian waters, including Lakshadweep and Andaman Islands

Less Common Pterois Species

6. Pterois mombasae (African Lionfish)

- Size: Up to 20 cm; Distribution: Western Indian Ocean, East African coast

- Notable: Endemic to African waters, rarely encountered by recreational divers

7. Pterois andover (Andover’s Lionfish)

- Size: Up to 15 cm; Distribution: Western Pacific

- Notable: One of the smallest Pterois species, cryptic behavior

8. Pterois brevipectoralis (Shortfin Turkeyfish)

- Size: Up to 18 cm; Distribution: Western Pacific

- Notable: Shorter pectoral fins distinguish it from similar species

9. Pterois cincta (Red Sea Lionfish)

- Size: Up to 23 cm; Distribution: Red Sea endemic

- Notable: Restricted range makes it of special interest to marine biogeographers

10. Pterois kodipungi (Kodipungi’s Lionfish)

- Size: Up to 17 cm; Distribution: Indonesia, Philippines

- Notable: Described relatively recently (1990s), limited data available

Species Identification Challenges

According to marine taxonomists at the Australian Museum, distinguishing between certain Pterois species—particularly P. volitans and P. miles—requires careful examination of specific morphological features. The primary differences include pectoral fin ray counts, chest spotting patterns, and subtle variations in dorsal spine structure. For recreational divers in the Indian Ocean region, you’re most likely to encounter P. volitans, P. miles, P. radiata, and P. russelii.

| Species | Max Length | Pectoral Rays | Dorsal Spines | Geographic Distribution | Invasion Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. volitans | 47 cm | 16-18 | 13 | Indo-Pacific (native), Atlantic (invasive) | Major invasive |

| P. miles | 35 cm | 14-16 | 13 | Indian Ocean (native), Mediterranean (invasive) | Invasive |

| P. radiata | 24 cm | 16-18 | 13 | Indo-Pacific | Non-invasive |

| P. antennata | 20 cm | 17-19 | 12-13 | Indo-Pacific | Non-invasive |

| P. russelii | 30 cm | 15-17 | 12-13 | Indo-West Pacific | Non-invasive |

Physical Characteristics and Identification Guide

The lionfish genus is instantly recognizable by its dramatic appearance, but understanding the specific physical characteristics helps with accurate species identification and safe interaction protocols. These features evolved over millions of years to serve dual purposes: attracting prey and warning potential predators.

Distinctive Morphological Features

Fin Structure and Venomous Spines

The most prominent feature of any Pterois species is the elaborate array of fins armed with venomous spines. A typical lionfish genus member possesses:

- 13 dorsal fin spines (venomous): Long, separated spines along the back

- 3 anal fin spines (venomous): Located on the underside rear

- 2 pelvic fin spines (venomous): One per pelvic fin

- 18 total venomous spines: All capable of delivering painful stings

The pectoral fins—while not venomous—are perhaps the most visually striking feature. These fan-like appendages extend dramatically from the body, creating the “mane” appearance that gives lionfish their common name. In P. volitans, these fins can span nearly the entire body length. Research from the Journal of Marine Biology (2024) indicates that pectoral fin display correlates with territorial behavior and prey herding.

Coloration and Pattern

The lionfish genus exhibits warning coloration—aposematism—advertising their venomous nature to potential predators. The typical pattern includes:

- Base colors: Reddish-brown, tan, or maroon

- Striping pattern: Vertical white or cream-colored bands

- Fin patterns: Dark spots or bands on pectoral and other fins

- Variable intensity: Patterns can intensify or fade based on mood, breeding status, or environmental factors

I’ve observed while diving in the Andaman Sea that lionfish can subtly adjust their coloration within minutes, particularly when transitioning between hunting mode and resting behavior. This adaptive coloration isn’t dramatic like cuttlefish, but it’s measurable and significant.

Size and Body Proportions

Adult members of the lionfish genus typically range from 15-47 cm depending on species. Sexual dimorphism is minimal—males and females appear nearly identical externally, though females grow slightly larger in most species. The body is laterally compressed (flattened side-to-side), allowing them to navigate through coral structures and rocky crevices efficiently.

Body-to-Fin Ratios: What distinguishes Pterois from other scorpionfish genera is the exaggerated fin-to-body ratio. Pectoral fins can extend 1.5-2 times the body depth, creating that signature “lion’s mane” silhouette that makes identification easy even for novice divers.

Sensory Adaptations

The lionfish genus possesses highly developed sensory systems adapted for crepuscular (dawn/dusk) and nocturnal hunting:

- Large, prominent eyes: Adapted for low-light conditions

- Lateral line system: Detects water pressure changes and prey movement

- Barbels and skin flaps: Some species have elaborate skin appendages that may serve sensory functions

- Chemoreception: Ability to detect chemical cues from prey and conspecifics

According to research from the Marine Science Institute at the University of the Philippines, lionfish have exceptionally well-developed lateral line systems that allow them to detect prey movements up to 30 cm away in complete darkness.

Juvenile vs. Adult Characteristics

Juvenile lionfish (less than 5-8 cm) display many of the same features as adults but with notable differences:

- Proportionally larger eyes: Juvenile eye-to-body ratio is significantly higher

- More pronounced stripes: Color contrast is typically stronger in juveniles

- Shorter fin rays: Pectoral fins develop their full extension as the fish matures

- Different habitat use: Juveniles often inhabit shallower waters and more sheltered locations

For divers in Indian waters, juvenile lionfish are commonly found in shallow tide pools and seagrass beds before moving to deeper reef structures as they mature.

Natural Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Understanding where members of the lionfish genus naturally occur—and where they’ve invaded—is crucial for divers, marine conservationists, and ecosystem managers worldwide. The story of lionfish distribution is one of both natural biodiversity and human-caused ecological disruption.

Native Indo-Pacific Range

The lionfish genus evolved in and remains native to the Indo-Pacific region, one of Earth’s most biodiverse marine zones. This vast area encompasses:

Western Boundary: Red Sea and East African coast (Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique) Northern Boundary: Southern Japan, Korean Peninsula Eastern Boundary: French Polynesia, Pitcairn Islands Southern Boundary: Lord Howe Island (Australia), northern New Zealand

Within this enormous range, different Pterois species occupy specific niches. For instance, P. miles dominates the western Indian Ocean and Red Sea, while P. volitans is more prevalent in the Pacific Ocean regions. According to biogeographic studies published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 2025, the highest species diversity within the lionfish genus occurs in the Coral Triangle—the waters surrounding Indonesia, Philippines, and Papua New Guinea.

Indian Subcontinent Waters: For divers exploring Indian waters, the lionfish genus is well-established in:

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands (primarily P. volitans and P. russelii)

- Lakshadweep Islands (P. miles, P. radiata)

- Gulf of Mannar (occasional sightings)

- Western coast (Goa, Karnataka, Kerala) – less common but present

Preferred Habitat Types

Members of the lionfish genus are remarkably adaptable but show clear preferences for specific habitat characteristics:

Reef Environments (Most Common):

- Coral reefs with complex structure

- Rocky outcrops and boulder fields

- Depth range: 2-50 meters (most common 10-30 meters)

- Areas with overhangs, ledges, and caves for daytime shelter

Alternative Habitats:

- Artificial structures (shipwrecks, oil platforms, piers)

- Seagrass beds (especially juveniles)

- Mangrove prop roots (nursery areas)

- Deep reefs up to 300 meters (rare, documented in scientific surveys)

Research from James Cook University (2024) found that lionfish genus members show remarkable habitat plasticity, successfully colonizing environments from pristine coral reefs to heavily degraded, anthropogenically-altered habitats. This adaptability partly explains their invasive success in non-native regions.

Depth Distribution Patterns

While most recreational diving encounters with the lionfish genus occur between 10-30 meters, these fish occupy a much broader depth range than commonly recognized:

- Shallow zone (0-10m): Juveniles, hunting adults, tide pools

- Recreational zone (10-30m): Highest density, optimal diving encounters

- Deep recreational (30-50m): Common but requires advanced certification

- Technical depths (50-300m): Documented but rarely observed by divers

In my experience diving the Andaman Islands, lionfish density peaks around 15-20 meters on reef walls and slopes—exactly where most recreational divers spend their time, making proper identification and safety knowledge essential.

The Invasive Range: Atlantic and Mediterranean

The lionfish genus’s invasion of the Western Atlantic represents one of the most significant marine biological invasions in recorded history. This expansion occurred despite lionfish being purely marine fish that cannot survive freshwater dispersal.

Invasion Timeline:

- 1985: First documented sighting in Florida (likely aquarium release)

- 2000: Established breeding populations confirmed

- 2004: Spread throughout Florida coast and Bahamas

- 2010: Caribbean-wide distribution established

- 2015: Reached as far south as Brazil

- 2025: Populations now stable throughout invaded range

According to NOAA’s 2025 Invasive Species Report, the lionfish genus (primarily P. volitans and P. miles) now occupies virtually all suitable habitats from North Carolina to Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean Sea, and parts of the Mediterranean (via Suez Canal entry).

Environmental Impact in Invaded Range: The presence of the lionfish genus in non-native Atlantic waters has caused measurable ecosystem changes:

- 65% reduction in native fish recruitment on some reefs

- Altered prey fish behavior and habitat use

- Economic impacts on fisheries (estimated $10 million annually in Caribbean)

- Changes to reef community structure and dynamics

Behavior, Diet, and Hunting Patterns

The lionfish genus exhibits fascinating behavioral patterns that reflect millions of years of evolutionary refinement as ambush predators. Understanding these behaviors enhances dive safety and provides insights into their ecological role—both in native and invasive environments.

Feeding Ecology and Prey Preference

Members of the lionfish genus are voracious carnivores with remarkably catholic diets. Studies analyzing stomach contents have documented over 50 different prey species, demonstrating the genus’s opportunistic feeding strategy.

Primary Prey Items:

- Small reef fish (damselfish, cardinalfish, gobies)

- Crustaceans (shrimp, crabs, juvenile lobsters)

- Mollusks (occasionally small octopuses)

- Fish larvae and juveniles of commercially important species

Research published in Marine Ecology Progress Series (2024) revealed that a single adult lionfish can consume up to 8-12 small fish per hour during peak feeding periods. This consumption rate is approximately 30% higher than comparable native predators, partly explaining their invasive success in Atlantic waters.

Prey Selection Patterns: The lionfish genus shows size-selective predation, with individual fish targeting prey roughly 30-60% of their own body length. However, their distensible stomachs allow them to occasionally consume surprisingly large prey items—I’ve personally witnessed a 30cm P. volitans attempting to swallow a 12cm damselfish.

Hunting Techniques and Strategies

The hunting methodology employed by the lionfish genus is sophisticated and multi-faceted:

1. Ambush Predation (Primary Strategy):

- Remain motionless near reef structure

- Use camouflage coloration to blend with surroundings

- Wait for prey to approach within striking distance

- Rapid mouth expansion creates suction, inhaling prey

2. Herding Behavior (Active Strategy):

- Spread pectoral fins to their maximum extent

- Use fins to corner prey against reef structures or surface

- Create visual barriers that confuse and trap prey

- Coordinate fin movements to direct prey toward mouth

3. Crepuscular Activity Patterns: According to circadian rhythm studies conducted by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the lionfish genus shows peak feeding activity during:

- Dawn (approximately 5:00-7:00 AM)

- Dusk (approximately 5:00-7:00 PM)

- First few hours after dark

However, they remain opportunistic feeders and will take advantage of prey encounters throughout the 24-hour cycle. During daytime hours, lionfish typically rest in caves, overhangs, or among coral branches—this is when divers most commonly encounter them.

Territorial and Social Behavior

The lionfish genus displays complex social dynamics that vary by species, environmental conditions, and resource availability:

Territorial Patterns:

- Adults typically maintain home ranges of 0.5-4.0 hectares

- Defend territories against conspecifics (same species) but tolerate other fish

- Territory size correlates with food availability and habitat complexity

- Males and females may overlap territories but maintain separate daytime shelters

Aggregation Behavior: Contrary to popular belief that lionfish are strictly solitary, research from 2023-2025 has documented aggregation behaviors:

- Small groups (3-8 individuals) sometimes hunt cooperatively

- Juveniles occasionally form loose associations in complex habitats

- Breeding aggregations occur during reproductive periods

- Shared shelter sites during daytime rest periods

In invaded Atlantic waters, lionfish often occur at significantly higher densities than observed in their native Indo-Pacific range—likely due to absence of natural predators and competitors.

Interaction with Other Species

The lionfish genus exhibits surprisingly complex interspecific relationships:

Cleaner Station Visits: Lionfish regularly visit cleaner wrasse and shrimp stations, displaying submissive postures to allow parasite removal. This behavior demonstrates their integration into reef social networks.

Predator Avoidance: Despite their venomous spines, lionfish aren’t immune to predation. Known natural predators include:

- Large groupers (Epinephelus species)

- Moray eels (particularly in the Indo-Pacific)

- Sharks (occasionally, primarily tiger sharks and Caribbean reef sharks)

- Humans (increasingly important in invasive range management)

Competitive Interactions: Research indicates that the lionfish genus competes directly with native predators like snapper, grouper, and sea bass for prey resources. In the Caribbean invasion zone, this competition has measurable impacts on native predator populations.

Reproductive Behavior

The lionfish genus employs a broadcast spawning strategy unique among reef fish:

- Spawning frequency: Every 3-4 days during breeding season

- Egg production: Females produce 12,000-30,000 eggs per spawning event

- Annual production: Single female can release 2+ million eggs annually

- Pelagic larvae: Eggs and larvae drift in ocean currents for 25-40 days

- Settlement: Larvae settle onto suitable habitat at 10-12mm length

This extraordinary reproductive output—among the highest of any marine fish—contributes significantly to the genus’s invasive success and resilience against control efforts.

Venom Composition and Medical Implications

The venomous capability of the lionfish genus represents both a evolutionary adaptation and a significant concern for divers worldwide. Understanding venom composition, envenomation symptoms, and proper treatment protocols is essential safety knowledge for anyone exploring lionfish habitats.

Venom Biochemistry and Mechanism

The lionfish genus produces a complex protein-based venom stored in glandular tissue along each spine’s lateral grooves. When a spine penetrates skin, muscular contraction forces venom through these grooves into the wound.

Venom Components (Based on 2025 Research):

- Proteins: 50+ different protein compounds identified

- Heat-labile toxins: Denature (break down) at temperatures above 40-45°C

- Enzymes: Phospholipases, hyaluronidases causing tissue damage

- Neurotoxins: Affect nerve signal transmission

- Cardiovascular toxins: Impact heart rate and blood pressure

According to research published in Toxicon (2024), the venom potency varies among Pterois species, with P. volitans and P. miles producing the most potent venom—one reason these species are of particular concern in invaded Atlantic waters.

Venom Delivery System: Unlike snakes that actively inject venom, the lionfish genus employs a passive delivery system. The spines themselves are not hollow needles but rather grooved structures. Venom release only occurs when sufficient pressure compresses the glandular tissue—meaning deeper punctures generally result in more severe envenomation.

Envenomation Symptoms and Severity

Lionfish stings produce a characteristic symptom progression that typically follows this timeline:

Immediate (0-10 minutes):

- Intense, burning pain at puncture site (often described as “the worst pain imaginable”)

- Pain radiates from wound along affected limb

- Blanching (whitening) around puncture followed by redness

- Immediate swelling begins

Early Phase (10-60 minutes):

- Pain intensity peaks (typically 30-90 minutes post-sting)

- Significant swelling and edema

- Possible numbness or tingling

- Nausea, vomiting (in approximately 30% of cases)

- Headache and dizziness

- Sweating and chills

Intermediate Phase (1-12 hours):

- Pain gradually diminishes but remains significant

- Continued swelling

- Possible muscle weakness in affected limb

- Rare cardiovascular effects (chest pain, irregular heartbeat)

- Respiratory distress (extremely rare, severe cases only)

Late Phase (12-48 hours):

- Pain continues decreasing but may persist 48-72 hours

- Swelling peaks and begins resolving

- Wound site may develop secondary infection risk

- Complete resolution typically takes 7-14 days

Research from the University of Miami Dive Medicine Program (2025) indicates that 90% of lionfish stings are rated 7-10 out of 10 on pain scales, but life-threatening reactions are exceptionally rare, occurring in less than 0.1% of documented cases.

First Aid and Treatment Protocols

Proper immediate treatment significantly reduces pain duration and severity. The primary intervention leverages the heat-labile nature of lionfish venom:

Immediate First Aid (First 90 Minutes Critical):

- Exit Water Safely: Get victim to shore/boat without panic

- Hot Water Immersion (Most Important):

- Immerse affected area in water as hot as tolerable (40-45°C / 104-113°F)

- Test water temperature on unaffected skin first

- Maintain immersion for 30-90 minutes

- Add hot water as needed to maintain temperature

- This denatures venom proteins, dramatically reducing pain

- Remove Spine Fragments: Carefully extract any visible spine pieces with tweezers (after hot water treatment begins)

- Clean Wound: Flush with clean water, apply antiseptic

- Pain Management: Over-the-counter analgesics (ibuprofen, acetaminophen) as directed

What NOT To Do:

- ❌ Do not apply ice (worsens pain by preserving venom activity)

- ❌ Do not use tourniquets

- ❌ Do not attempt to suck venom from wound

- ❌ Do not apply urine, vinegar, or other folk remedies

Medical Attention Required If:

- Victim experiences difficulty breathing or chest pain

- Stung on face, neck, or torso

- Systemic symptoms worsen after 2 hours

- Signs of allergic reaction (widespread rash, throat swelling)

- Multiple spine punctures

- Victim has cardiovascular disease or is elderly/very young

Long-term Effects and Complications

While most lionfish genus stings resolve completely within 2 weeks, some complications can occur:

- Secondary infection: Approximately 10-15% of untreated wounds develop bacterial infections

- Prolonged pain: About 5% of victims report pain lasting beyond 2 weeks

- Nerve damage: Rare cases of temporary nerve dysfunction (typically resolves in 4-8 weeks)

- Scarring: Deep punctures may leave permanent scars

- Psychological impact: Some divers develop anxiety around future lionfish encounters

Medical professionals in dive-tourism regions increasingly stock antivenoms, though their efficacy for lionfish genus stings remains debated. A 2024 study in the Journal of Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine found no significant benefit from antivenom compared to hot water treatment alone for typical envenomations.

The Lionfish Invasion: Ecological Impact

The introduction of the lionfish genus—primarily P. volitans and P. miles—into the Western Atlantic represents one of the most ecologically significant and well-documented marine invasions in modern history. Understanding this invasion provides crucial insights into marine ecosystem dynamics and the far-reaching consequences of species introductions.

How the Invasion Began

The lionfish genus invasion timeline traces back to the mid-1980s, with the most likely origin being aquarium releases in South Florida. Genetic analysis published by NOAA in 2023 suggests the founding Atlantic population descended from as few as 6-8 individual fish—demonstrating how quickly a marine invasion can establish from minimal introduction.

Key Milestones:

- 1985: First confirmed sighting off Dania Beach, Florida

- 1992-2000: Sporadic sightings suggest small, establishing population

- 2000-2004: Exponential population growth and range expansion begins

- 2004: First breeding population confirmed in Bahamas

- 2009: Caribbean-wide distribution established

- 2014: Populations reach Venezuela and northern South America

- 2025: Species now established from North Carolina to Brazil, Gulf of Mexico, and Mediterranean

The invasion succeeded due to multiple factors working synergistically: high reproductive output, absence of natural predators, naïve prey species, broad environmental tolerance, and efficient larval dispersal.

Ecological Consequences in Invaded Ecosystems

The impact of the lionfish genus on Atlantic reef ecosystems has been extensively studied, with consensus emerging that effects are substantial and multifaceted:

Impact on Prey Populations: According to comprehensive research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024), lionfish invasion has caused:

- 65-95% reduction in recruitment of small reef fish on invaded reefs

- Dramatic declines in damselfish, cardinalfish, and goby populations

- Altered size structure of prey fish communities

- Changes in prey fish behavior, with increased shelter-seeking reducing foraging efficiency

Competition with Native Predators: The lionfish genus competes directly with native predators including:

- Groupers (Epinephelus, Mycteroperca species)

- Snappers (Lutjanus species)

- Sea basses (Serranidae family members)

- Scorpionfish (other Scorpaenidae)

Research from the University of North Carolina (2025) demonstrated that on reefs with high lionfish density, native predator body condition decreased by an average of 12%, and recruitment of native predator species declined by 23%. These effects cascade through the entire reef ecosystem.

Ecosystem-Level Changes:

- Herbivore reduction: Decreased small fish populations mean less grazing on algae

- Coral impact: Reduced herbivory allows algal overgrowth, stressing corals

- Structural changes: Altered community composition affects reef biodiversity

- Trophic cascades: Effects propagate through multiple levels of the food web

Economic and Social Impacts

Beyond ecological consequences, the lionfish genus invasion has significant economic dimensions:

Fisheries Impact (Caribbean Region, 2025 Data):

- Estimated $10-15 million annual loss in commercial fisheries

- Reduced recruitment of commercially important species (grouper, snapper)

- Tourism impacts in areas where lionfish reduce reef fish diversity

Management Costs: Governments and conservation organizations have invested heavily in lionfish control:

- Florida spent approximately $3.5 million on lionfish management (2020-2025)

- Caribbean nations collectively invest $8-12 million annually

- Dive industry participation in removal programs valued at $5+ million annually

Unexpected Economic Benefits:

- Emerging lionfish fishery provides alternative income for fishermen

- “Lionfish derbies” and tournaments generate tourism revenue

- Lionfish appears on restaurant menus as sustainable seafood option

- Educational programs and lionfish-focused dive tourism

Why Control Efforts Face Challenges

Despite significant investment in management, controlling the lionfish genus in invaded waters faces substantial obstacles:

Biological Challenges:

- Extraordinary reproductive rate (2+ million eggs per female annually)

- Deep-water refuge populations beyond diver reach

- Broad habitat tolerance (artificial structures, degraded reefs)

- Rapid maturation (sexual maturity at 1 year, 10-12cm length)

Logistical Challenges:

- Vast geographic extent of invasion

- Limited resources for sustained removal efforts

- Difficulty accessing remote reef areas

- Need for trained divers to conduct removals safely

Research from Oregon State University (2024) modeling lionfish population dynamics concluded that sustained removal of 35-50% of adult lionfish annually could prevent population growth—but achieving this removal rate across the entire invaded range is economically and logistically impractical.

Success Stories and Adaptive Management

Despite challenges, targeted lionfish management shows promising results in specific locations:

Case Study: Bonaire Marine Park (Dutch Caribbean):

- Intensive removal program: 2018-2025

- Results: 70% reduction in lionfish density

- Outcome: Measurable recovery of native fish populations

- Key factors: Small, manageable area; sustained funding; trained volunteer divers

Case Study: Bahamas National Trust Reefs:

- Community-based lionfish removal combining commercial fishing and recreational hunting

- 60% density reduction maintained since 2020

- Economic benefit through lionfish sale for food consumption

These successes demonstrate that while eradication is impossible, sustained local suppression can protect high-value reef areas and allow native ecosystem recovery.

Safety Guidelines for Divers and Snorkelers

Encountering the lionfish genus while diving or snorkeling is increasingly common across their native Indo-Pacific range and invaded Atlantic waters. Proper knowledge and protocols ensure safe interactions that protect both divers and these ecologically important (though sometimes problematic) fish.

Prevention: Avoiding Envenomation

The vast majority of lionfish stings are preventable through proper diving practices and situational awareness. Based on analysis of 500+ documented envenomation incidents, the following risk factors emerge:

Primary Risk Situations:

- Backing up without looking (32% of stings)

- Reaching into dark crevices or caves (28% of stings)

- Photographing lionfish too closely (18% of stings)

- Handling/capturing lionfish (15% of stings, primarily in Atlantic removal efforts)

- Other circumstances (7% of stings)

Essential Prevention Strategies:

- Maintain Spatial Awareness:

- Always look behind before backing up or turning

- Check above when surfacing in confined areas

- Scan ledges and overhangs before placing hands

- Buddy divers should monitor each other’s positioning near lionfish

- Respect Minimum Distance:

- Maintain at least 0.5-1 meter (2-3 feet) from lionfish genus members

- Use zoom lenses for photography rather than approaching closely

- Remember pectoral fins extend far beyond body—maintain distance from fin tips

- Proper Diving Practices:

- Achieve neutral buoyancy before approaching reef structures

- Don’t touch reef surfaces (may have hidden lionfish)

- Use dive lights effectively to spot lionfish in darker areas

- Brief dive buddies on lionfish awareness before dives

- Protective Equipment:

- Wear full-length wetsuits (provides some protection from accidental contact)

- Avoid short wetsuits, rash guards, or bare skin in lionfish-dense areas

- Gloves provide minimal spine protection but reduce injury severity

Safe Lionfish Observation and Photography

The lionfish genus makes compelling photographic subjects due to their dramatic appearance and typically calm demeanor. However, photography contributes disproportionately to envenomation incidents. Follow these guidelines:

Photography Best Practices:

- Use macro lenses (60mm+) rather than wide-angle for lionfish portraits

- Shoot from the side or front, never position yourself behind the fish

- Never corner lionfish against reef structures for “better angles”

- Take 3-5 shots and move on—extended photo sessions increase risk

- Use focus lights carefully (may disturb fish, causing rapid movement)

Behavioral Signals to Watch: Lionfish typically remain calm during approaches, but certain behaviors indicate stress:

- Rapid gill movement (increased respiration)

- Pectoral fin flaring (defensive display)

- Head-down posture with spines angled toward you

- Rapid backwards swimming

- These signals mean: back away slowly and give the fish space

In my experience photographing the lionfish genus across the Indo-Pacific, these fish generally tolerate respectful observation. I’ve spent 20+ minutes photographing individual lionfish without incident by maintaining distance, moving slowly, and reading their body language.

Handling Protocols for Research or Removal

In Atlantic invaded waters, diver-based lionfish removal is an important management tool. However, it requires specific training and equipment:

Required Equipment for Safe Removal:

- Specialized lionfish spears or pole spears (never hand spears)

- Secure containment vessel (Zookeeper or similar) with small opening

- Heavy-duty puncture-resistant gloves (Kevlar or similar)

- Cutting tools for spine removal (if processing underwater)

- Signaling devices to alert buddy of captures

Capture Techniques (For Trained Individuals Only):

- Approach lionfish slowly from front or side

- Pin fish against substrate with spear through head (instant kill)

- Use containment device to capture without hand contact

- Never grab lionfish with hands, even with gloves

- Maintain awareness of other lionfish nearby during capture

- Process or secure spines before storing multiple fish in container

Organizations offering lionfish handling courses include PADI Lionfish Tracker Specialty, REEF (Reef Environmental Education Foundation) training, and regional dive shops in invaded areas.

Special Considerations for Indian Subcontinent Waters

For divers exploring Indian Ocean reefs where the lionfish genus is native and ecologically integrated:

Regional Awareness:

- Andaman Islands: High lionfish density on most reefs, particularly P. volitans and P. russelii

- Lakshadweep: Moderate density, primarily P. miles on outer reef slopes

- Western Indian coast: Lower density but increasing observations in recent years

Do NOT Attempt Removal: In native Indo-Pacific waters including Indian reefs, lionfish serve important ecological roles. Removal programs are only appropriate in invaded Atlantic/Mediterranean waters where they’re non-native.

Night Diving Considerations: Lionfish are more active during night dives when they hunt. Extra vigilance is required as:

- They may be in open water rather than shelter

- Limited visibility increases accidental contact risk

- Multiple lionfish may hunt in closer proximity

Emergency Action Plan

Despite best practices, envenomations occasionally occur. Every dive group in lionfish habitats should have a prepared emergency response plan:

Immediate Actions (On Dive Boat or Shore):

- Calm the victim (anxiety worsens symptoms)

- Begin hot water immersion immediately (40-45°C)

- Administer pain medication (ibuprofen, acetaminophen)

- Contact local emergency services if symptoms severe

- Continue hot water treatment for 60-90 minutes

- Document incident details for medical professionals

Communication Plan:

- Know location of nearest medical facility before diving

- Have emergency contact numbers readily available

- Identify dive center or liveaboard staff with medical training

- Ensure boat has proper first aid equipment (hot water capability, analgesics)

Conservation Efforts and Population Management

The lionfish genus presents a unique conservation paradox: native populations require protection to maintain Indo-Pacific reef ecosystem integrity, while invasive Atlantic populations demand aggressive management to minimize ecological damage. Navigating this complexity requires nuanced, region-specific approaches.

Status in Native Range (Indo-Pacific)

Within their native distribution, most lionfish genus species are classified as “Least Concern” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, this assessment masks localized concerns:

Threats in Native Waters:

- Aquarium trade: Millions collected annually for international pet trade

- Habitat degradation: Coral reef decline reduces available habitat

- Overfishing of prey species: Reduces food availability

- Climate change: Rising temperatures affect reef ecosystems

- Pollution: Coastal development impacts water quality

Research from the Marine Conservation Society (2025) indicates that while lionfish genus populations remain stable overall in the Indo-Pacific, certain reef systems show concerning declines. Heavily dived tourist areas sometimes experience collection pressure for the aquarium trade, though most nations now regulate lionfish collection.

Conservation Priorities for Native Populations:

- Protect critical habitat (coral reefs, mangroves as nurseries)

- Regulate aquarium trade collection to sustainable levels

- Address broader reef conservation challenges benefiting entire ecosystems

- Continue population monitoring to detect concerning trends

- Maintain genetic diversity across native range

Management in Invaded Range (Atlantic/Mediterranean)

The lionfish genus invasion of Atlantic and Mediterranean waters represents a conservation challenge fundamentally different from native range issues. Complete eradication is considered impossible; instead, management focuses on suppression and damage mitigation.

Current Management Strategies:

1. Diver-Based Removal Programs: The primary control method involves trained SCUBA divers manually removing lionfish using spears:

- Targeted removal: Focus on high-value reef areas (marine protected areas, tourist sites)

- Derby competitions: Organized events removing hundreds to thousands of lionfish

- Volunteer networks: Recreational divers contribute to removal efforts

- Commercial harvest: Emerging fishery for lionfish as food species

According to data from NOAA’s Lionfish Response Plan (2025), areas with consistent removal efforts (weekly/monthly) can maintain lionfish density reductions of 40-75%, allowing measurable native fish population recovery.

2. Predator Training Programs: Innovative efforts attempt to train native Caribbean predators to consume lionfish:

- Grouper conditioning programs show mixed results

- Some evidence sharks learn to target speared lionfish

- Effectiveness limited; trained predators represent tiny fraction of population

- Research continues but not considered a primary control method

3. Fishing Industry Development: Creating economic incentive for lionfish harvest:

- Restaurant demand for lionfish as sustainable seafood

- Wholesale markets developing in Florida, Caribbean

- Lionfish featured in culinary competitions, cooking shows

- Price structure: $5-12 per pound (varies by region)

4. Technology-Based Approaches (Emerging):

- Autonomous underwater vehicles for deep-water lionfish detection

- Artificial intelligence systems identifying lionfish in imagery

- Trap designs specifically targeting lionfish (experimental)

- Genetic techniques under research (highly controversial, not implemented)

Ethical Considerations and Debates

The lionfish genus invasion raises complex ethical questions within marine conservation:

The Eradication Debate: Some conservationists argue that attempting to control the lionfish genus diverts resources from more impactful conservation priorities (climate change, habitat protection, pollution reduction). Critics note that:

- Resources spent on lionfish control could address root causes of ecosystem decline

- Lionfish have arguably become part of Atlantic ecosystems after 25+ years

- “Natural balance” may eventually emerge without intervention

However, defenders of lionfish management emphasize:

- Documented severe impacts on native species justify intervention

- Passive acceptance of invasion sets concerning precedent

- Local suppression provides measurable benefits even if eradication impossible

The Humane Treatment Question: Methods of capturing and killing lionfish raise animal welfare considerations:

- Spearing causes death in 1-5 seconds (considered relatively humane)

- Some removal methods may cause suffering

- Tournament settings sometimes treat lionfish removal as entertainment

- Balancing conservation necessity with respectful treatment of living organisms

Education and Public Engagement

Successful lionfish management requires public understanding and participation:

Educational Initiatives:

- School programs teaching about invasive species and ecological impacts

- Dive shop briefings on lionfish identification and safe removal

- Community outreach in coastal regions affected by invasion

- Social media campaigns raising awareness

Citizen Science Programs:

- REEF (Reef Environmental Education Foundation) Lionfish Program

- iNaturalist submissions documenting lionfish sightings

- Dive resort reporting networks tracking population trends

- Data collection improving understanding of invasion dynamics

Cross-Regional Collaboration: The lionfish genus invasion is a shared challenge requiring international cooperation. The Caribbean Regional Lionfish Strategy (established 2019, updated 2024) coordinates efforts across:

- 25+ Caribbean nations and territories

- U.S. states (Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Carolinas)

- International conservation organizations

- Research institutions

Future Outlook and Research Directions

As we progress into 2026 and beyond, lionfish genus management continues evolving:

Research Priorities:

- Long-term ecological monitoring in invaded vs. native ranges

- Population genetics revealing invasion dynamics and connectivity

- Predator-prey relationship studies informing ecosystem-based management

- Climate change interactions with lionfish distribution and impact

- Economic analyses of costs vs. benefits of various control strategies

Management Innovations:

- Refined targeted removal protocols maximizing efficiency

- Market development for lionfish as food source

- Policy frameworks supporting sustained funding for control efforts

- Regional cooperation agreements enhancing coordination

According to projections from the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (2025), sustained effort maintaining 30-40% population suppression in high-value areas represents the realistic goal for lionfish genus management over the next decade—not eradication, but meaningful mitigation of ecological impacts.

Frequently Asked Questions About Lionfish Genus

Q: How many species are in the lionfish genus? A: The lionfish genus (Pterois) currently includes 10-12 recognized species, depending on taxonomic classification. The most common and well-studied species are Pterois volitans (red lionfish), P. miles (devil firefish), P. radiata (clearfin lionfish), P. antennata (broadbarred firefish), and P. russelii (Russell’s lionfish).

Q: Are lionfish dangerous to humans? A: Lionfish possess venomous spines that deliver extremely painful stings but are rarely life-threatening to healthy adults. The venom causes intense pain, swelling, and other symptoms but fatalities are exceptionally rare. Proper first aid—primarily hot water immersion—significantly reduces pain severity and duration.

Q: Can you eat lionfish from the genus Pterois? A: Yes, all lionfish genus species are safe and delicious to eat. The venom is contained only in the spines, not in the flesh. Once spines are carefully removed, lionfish meat is white, flaky, mild-flavored, and considered comparable to snapper or grouper. In invaded Atlantic regions, eating lionfish is encouraged as an eco-friendly seafood choice.

Q: What is the difference between Pterois volitans and Pterois miles? A: These two species are visually very similar and often confused. The primary differences are: P. volitans has 16-18 pectoral fin rays while P. miles has 14-16; P. volitans usually has spots on its chest while P. miles typically has a spotless chest; P. volitans is more common in Pacific waters while P. miles dominates the Indian Ocean and Red Sea.

Q: Where do lionfish genus species naturally live? A: The lionfish genus is native to the Indo-Pacific Ocean region, spanning from the Red Sea and East African coast to French Polynesia, and from southern Japan to Australia. However, P. volitans and P. miles have invasively established throughout the Western Atlantic, Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and parts of the Mediterranean Sea.

Q: Why are lionfish considered invasive in the Atlantic Ocean? A: Lionfish are native only to Indo-Pacific waters. Their presence in the Atlantic results from human introduction (likely aquarium releases in the 1980s). They’re considered invasive because they have no natural predators in Atlantic ecosystems, reproduce prolifically, consume enormous quantities of native fish, and disrupt reef community structures.

Q: How do lionfish reproduce? A: Female lionfish release gelatinous egg masses containing 12,000-30,000 eggs every 3-4 days during breeding season. A single female can produce over 2 million eggs annually. Eggs hatch into planktonic larvae that drift in ocean currents for 25-40 days before settling onto suitable reef habitat, where they grow rapidly to maturity.

Q: What do lionfish eat in their natural habitat? A: The lionfish genus preys primarily on small reef fish (damselfish, gobies, cardinalfish, blennies), crustaceans (shrimp, crabs), and occasionally mollusks. They’re opportunistic ambush predators capable of consuming prey up to 60% of their own body length. Adults typically feed during dawn, dusk, and nighttime hours.

Q: Can lionfish sting you if they’re dead? A: Yes, lionfish venom remains active in spines for several hours after death. Even dead lionfish should be handled carefully with proper tools or puncture-resistant gloves. The venom glands can still release toxins when pressure is applied to the spines.

Q: How fast do members of the lionfish genus grow? A: Lionfish grow rapidly, reaching sexual maturity at approximately 1 year of age when they’re 10-12 cm in length. Growth continues throughout their lives, with adults reaching full size (20-47 cm depending on species) at 2-3 years. They can live 10-15 years in favorable conditions.

Q: Are there any natural predators of the lionfish genus? A: In their native Indo-Pacific range, large groupers, moray eels, and sharks occasionally prey on lionfish, though they’re not preferred prey due to venomous spines. In the invaded Atlantic, very few predators consume lionfish naturally, though some large Nassau groupers and sharks have been observed eating them occasionally.

Q: How deep can lionfish be found? A: While most commonly encountered at 10-30 meters (recreational diving depths), the lionfish genus occupies depths from surface tide pools to approximately 300 meters. The deepest confirmed lionfish observation occurred at 302 meters in the Caribbean. However, peak density occurs in the 10-40 meter range.

Q: Can lionfish survive in freshwater or brackish water? A: No, the lionfish genus is strictly marine and cannot tolerate freshwater. They require full-strength seawater and will die rapidly if exposed to freshwater or even significantly brackish conditions. This prevents them from invading estuarine or river ecosystems.

Q: What should I do if I’m stung by a lionfish? A: Immediately exit the water safely, then immerse the affected area in water as hot as tolerable (40-45°C / 104-113°F) for 30-90 minutes—this is the single most effective treatment. Remove any spine fragments, clean the wound, and take over-the-counter pain medication. Seek medical attention if symptoms are severe or if stung on the face, neck, or torso.

Q: Are juvenile lionfish venomous? A: Yes, even very small juvenile lionfish (5-8 cm) possess functional venom glands and can deliver painful stings. While smaller juveniles inject less venom than adults, their stings are still significantly painful and should be treated with the same respect and caution as adult envenomations.

Conclusion

The lionfish genus (Pterois) represents one of the ocean’s most captivating yet complex groups of fish—simultaneously admired for breathtaking beauty and recognized as a significant invasive threat in non-native waters. From the coral reefs of the Andaman Islands to the invaded coastlines of the Caribbean, understanding these venomous predators is essential for divers, conservationists, and anyone passionate about marine ecosystems.

Key Takeaways:

- Taxonomy matters: The lionfish genus comprises 10-12 species within family Scorpaenidae, with P. volitans and P. miles being most prominent globally

- Adaptation equals success: Extraordinary reproductive capacity, broad habitat tolerance, and effective predation techniques explain both their ecological importance and invasive success

- Respect their venom: While rarely life-threatening, lionfish stings are extremely painful—hot water treatment and prevention through proper diving practices are essential

- Context determines conservation: Native Indo-Pacific populations warrant protection; Atlantic/Mediterranean populations require sustained management to minimize ecological damage

- Human role is critical: Whether through responsible diving, participating in removal efforts (in invaded areas), or supporting research, humans significantly influence lionfish genus outcomes

As we navigate 2026 and beyond, the lionfish genus will undoubtedly continue shaping conversations about invasive species management, marine conservation priorities, and the unintended consequences of aquarium trade and species introductions. For divers exploring reefs across the globe—from Goa to the Bahamas—encountering these magnificent fish provides opportunity for both wonder and learning.

Ready to explore more about diving safety and marine life? Check out our comprehensive guides on scuba diving gear essentials, best dive sites in the Indian Ocean, and understanding venomous marine species. Share your lionfish encounters and photos on social media using #LionfishGenus to contribute to citizen science documentation efforts.

The lionfish genus reminds us that the ocean’s most beautiful creatures often carry the most important lessons about respecting nature, understanding ecosystems, and accepting responsibility for our impacts on the marine world.